Yes, They Shoot Them. And They Eat Them.

Trigger (as in Roy Rogers) warning: This is about horses.

I’ve never been much of a horse person. I find them noble and all that, and I like the smell of their shit – when it’s dry and mixed with stable hay or in a country field, not the fresh wet plops – but they play no significant role in my life. I haven’t been on one since I was twelve. The only time I see them – or think about them – is when I bet on them.

Or at a gilets jaunes street protest.

I’m particularly wary of police horses. This dates to my childhood: when I was five my parents took me to Stanley Park, and while standing outside the Third Beach concession a Canadian Mountie’s horse kicked me in the head. A glancing blow, no doubt permanently damaging but not life-threatening. And entirely my fault: I was in the no-go zone behind the horse’s hind hooves, admiring its backside, nose close, and not offering it any of my creamsicle.

I probably would have kicked me in the head, too.

So, no, not a horse person. On occasion, however, I will eat one. Or rather, small pieces of one. The first of these were just as memorable as anything Proust ever got down him: three tender slices of tongue in a delicious mushroom cream sauce, served to me on the first night of my first European tour – a high-school rugby trip – by the rugby coach’s wife in the Paris suburb of Maisons-Laffitte, in 1977.

I had gone to market with the coach’s wife earlier in the day. Maisons-Laffitte is an affluent community, known as the “cité du cheval” because of its horse breeding and racetrack. It is also, I have just learned, the birthplace of the poet, playwright, novelist, designer, filmmaker, visual artist and critic Jean Cocteau, the actress Emma Watson, and the convicted sex trafficker Ghislaine Maxwell.

The covered market in the centre of town was unlike anything I’d ever seen, filled with delectables I couldn’t identify – so many dizzying heaps, piles and towers of fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, sausages, cheese, birds, breads and pastries that I was overcome by the same admiration and disbelief that Boris Yeltsin must have felt 12 years later, during his unscheduled 20-minute visit to a Randall's in Texas, when he saw the supermarket’s frozen food section.

Did Madame Entraîneur know in advance that she would be cooking a horse’s tongue that night? No idea. Nor did I know at the time that she was buying a horse’s tongue, even though I’m sure the butcher shop we were in was a boucherie chevaline, with a sign on its facade like the one below.

In my defence I was jet-lagged. And 17. And as yet untouched by the French language, much to le chagrin of Mesdames Graham (Grade 8), Parker (Grade 9) and Labbé (Grade 10).

“Langue,” said Madame Entraîneur during dinner that evening, after I polished off everything on my plate and made a mangled attempt to compliment her cuisine. “Du cheval.”

I had no idea what she was trying to tell me. Something to do with long hair?

“Cheveux?” I said, pulling at a few strands of my hockey mullet.

“Cheval,” she repeated, and her 12-year-old daughter – who like every other member of the family lit up a Gitane cigarette after each of the meal’s four courses – made a very convincing whinnying sound.

Cheval. Horse. Of course. Wow. Weird.

I was unaware that eating horse was a thing. Which it very much was and is. Not in Anglo Saxon countries, except by mistake or scam. But almost everywhere else.

In France, horse has graced plates since the Revolution. Napoleon, following the example of the Roman legions, fed it to his Grand Army. At Aspern-Essling in 1809, his first personal defeat, he instructed his army surgeon to cook horse bouillon on the breastplates of fallen cuirassiers, season it with gunpowder, and feed it to the wounded.

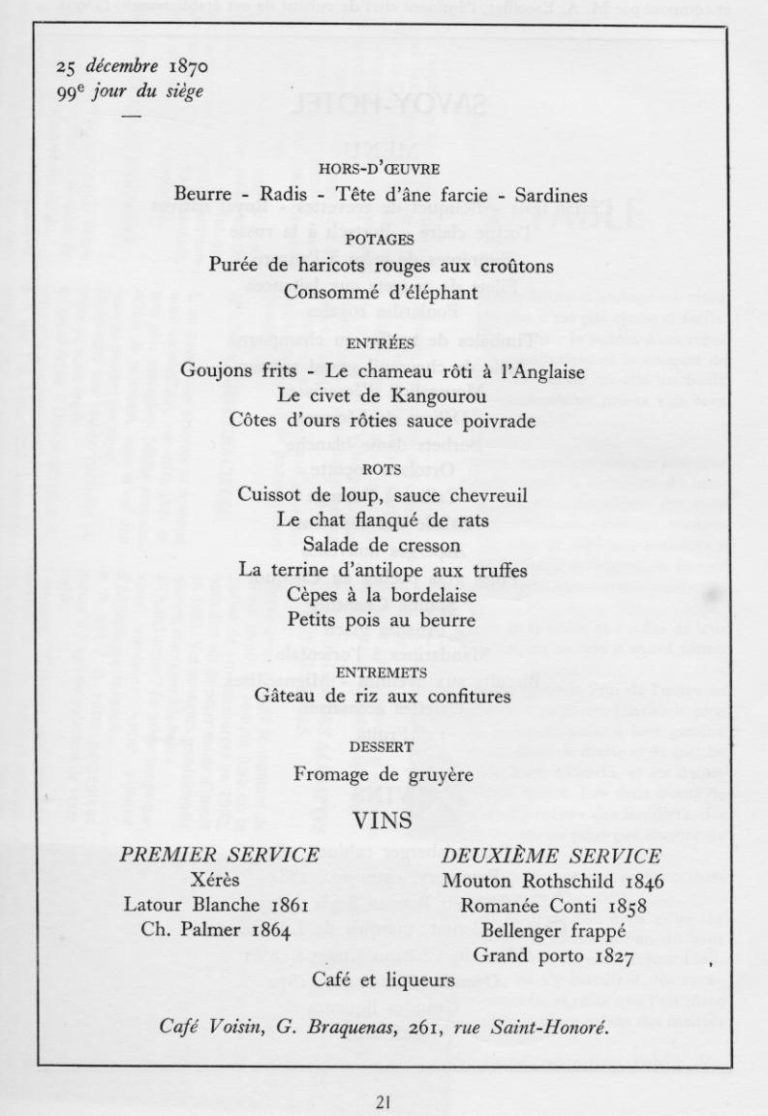

Horse meat consumption spiked during the siege of Paris in 1870, when the city’s starving citizens ate around 70,000, along with every available rat, cat, dog and all the city zoo animals, including its bears, elephants, and giraffes.

Hippophagy – the practice of eating horse meat – peaked in France around the turn of the century, when there were more than 300 chevalines and 200 horse meat market stalls in Paris. Those numbers have since decreased. In 2005 there were over a 1,000 horse butchers in France. By 2019 there were only 304. The reasons: as elsewhere, concern about health, animal welfare and climate change has resulted in French people, especially young French people, eating less meat.

Overall meat consumption has dropped 12% in the last decade (horse meat consumption goes down each year at a rate of around 12%).

The meat the French still eat is not the same, either. Because, apparently, most French people don’t like to cook, and when they have to they try to do so as quickly as possible. So they use more quick-prep stuff like minced beef and lardon chunks. They’re also less likely to eat game, offal, and horse, because, well, eating game, offal, and horse is weird. Especially horse. Why? Horses are Olympic athletes. They have special relationships with socially advantaged young girls. They don’t work in fields. They race around tracks for enormous amounts of money.

Hence, fewer chevaline butchers, which means higher prices for horse meat - the average price is around 18.50 euros a kilo, making it the second most expensive meat in France, only surpassed by veal. So, even those who like horse meat, are less likely, or able, to eat it.

To counter this trend, France has upped its exportation of live horses for slaughter. Mostly to Italy, some to Spain — the top two consumers of horse meat in Europe — the rest to Japan, the world’s second biggest horse eater, second to China.

The biggest shipper of meat horses is my home country, Canada – Alberta, mostly – which ships off thousands every year. The conditions, by most reports, are “sinister”. Canada also slaughters 25,000 horses each year for meat, which it freezes and ships. Some of the meat stays in Canada – horse meat is still a thing in Quebec – but most goes to Japan and France.

France. This is the weird bit: almost all the horse meat consumed in France is imported; and almost all the horse meat butchered in France is exported. Can anyone out there explain why? I spent a bunch of time recently researching global supply chains for an OECD podcast I hosted, but these sorts of dynamics didn’t come up. Is it price? Is it because French consumers prefer red horse meat, i.e., meat from an adult animal, and not pink foal meat, from horses less than two years of age, which is preferred in Japan? Anyone?

Ok, don’t know about you, but this subject is starting to make me feel a little queasy. No, that’s a lie. I’ve been feeling a little queasy ever since midnight last Monday, when, having slipped out of a side angle of the Hexagon for a three-day "Tutto Banger Niente Filler" tour of Italy, I found myself at a table in a late-night restaurant in Sicily that specialises in horse meat. And that’s why I’m here now, queasily reliving my first French dish and every bit of horse consumed since, and all of it now fodder for this piece.

The trip, a birthday present from two amazing but crazy friends, took us to many of the best restaurants and wine bars in Catania, Palermo, Rome, Bologna and Milan (become a paid subscriber and I’ll send you a list today!). It was a somewhat carbon-heavy indulgence (flight from to Catania, flight from Palermo to Rome) with more aperativos, full-menu-plus-everything-on-the-blackboard meals, and digestivos in three days than any sane person would attempt to consume in… two weeks? A month? A lifetime? In our defence, none of us drives a car, we took trains for the most part, and two of us went on three-day penitential purges immediately after (the third of our party, an absurdly big eater whose prodigious appetite has been described here before (and is profiled here in the Financial Times) just kept chewing and powered through).

At the Catania restaurant, one of nine in the city specialising in horse meat, we came upon our undoing: six of the house’s famous polpette di cavallo. Three semplice, three filled with “Philadelphia&Pistacchio”. All flame-scorched on the outside. All barely warm and raw and gristly on the inside.

Warning: the image below contains graphic content that might shock, offend, upset and disgust.

Whoops, too late, there it is.

Most of the balls and the remnants of the balls not on this plate I palmed into my napkin, slipped into the little envelope the cutlery came in, and left on the street outside for the Catanian cats. I doubt they ate them. If they did, I doubt they survived.

The two bites I took – one of each variety, just to be sure – were easily the least agreeable of my life.

I don’t care if it was my first French dish - my madeleine - or that it has twice as much iron as steak and around the same amount of omega-3 fatty acids as salmon. I don’t care if it’s pink or red, smoked and boiled, wrapped raw in a shiso leaf or cut into steaks and served with perfect frites.

My horse-eating days are done.

Probably.

Great piece! Did you try cavallo pestato? In Modena I was told that a REAL steak tartar was pestled--and not ground--horse meat because, after all, the Tatars didn't ride steers. It was excellent!

I recall coming across horse meat ( and some of those parts) in a market in Venice . I also recall then wondering about the origin of the cryptically described’roast ‘ we had ordered the night before at dinner.