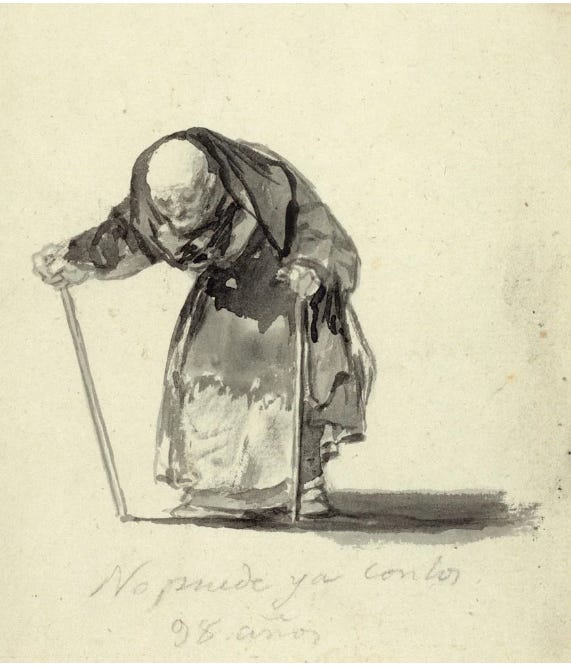

Recién llegados (“Recent Arrivals”), now lost, was cut out of the second Bordeaux sketchbook. It was drawn two weeks before his death. Written on the back: “La borboteante acequia de la calle del Desengaño da sustento a una piara de cerdos semisantos del Convento de San Antonio Abad.” (“The gurgling ditch on Calle del Desengaño provides sustenance to a herd of semi-holy pigs from the Convent of St Anthony the Abbot.”)

The drawing, in iron gall ink and pencil, is of two young peasant women – “Recién llegados a Madrid desde Aragón” – huddling against the wind in the doorway of a shop. “PERFUMES Y LIQORES” is painted on the shop window. A plaque on the wall near the corner bears the street’s name: “CALLE DEL DESENGAÑO”.

The building, No. 1 on the “street of disillusion” in the Centro district of Madrid, is where he and Pepa lived from 1779 to 1800. Their heir, Javier, was born there in 1784. Francisco, the only other of their seven children to see more than six birthdays (five more were stillborn) died there of the pest at fifteen in 1795. Rosario, his goddaughter, died down the street, at No. 17, fifteen years after him, at the age of twenty-eight, in 1843. Her mother, his maid, Leocadia, died there thirteen years later, in 1856.

The scene is lit by a single streetlamp. The two streetwalkers, pinching their noses against the stench of the open sewer, look on in horror at the shit-eating pigs. Crosses dangle from their necks.

He is at a window on the first floor, in profile, wearing a cloth cap similar to the one he wears in Autorretrato con gorra (1824) (Prado, GW 1658), the “self-portrait” now believed to have been drawn by Rosario.

Later, though, hovering higher and still wearing the cap, he sees and draws himself getting up from the chair on the landing, climbing down the stairs and going out the door. Only now there is no perfume shop. No prostitutes. No streetlamps, no sewer-gorged pigs. No street. Instead, a mule track covered in powdery snow and winding steeply out of frozen sierra steadily upwards, through clusters of bare oaks outlined in ice and stunted firs mantled white.

At the brow of the hill, on the flat-topped summit, he has a view down into a cratered gorge with quarries on its edge; and beyond, the Balearic Sea, fifteen leagues to the east.

At the centre of the saucer-like gorge, beneath the last fugitive rays of the sun, crumbling houses huddle around a snow-capped church topped by two tiny cupolas. This is Fuendetodos, the village where he was born. Looking west, he sees the sweet prospect of Zaragoza, the Zaragoza of his childhood.

However, when he finally manages to open his eyes, which causes great strain and anxiety, he can’t see anything. He has to feel his way with his hands, which are misshapen, numb.

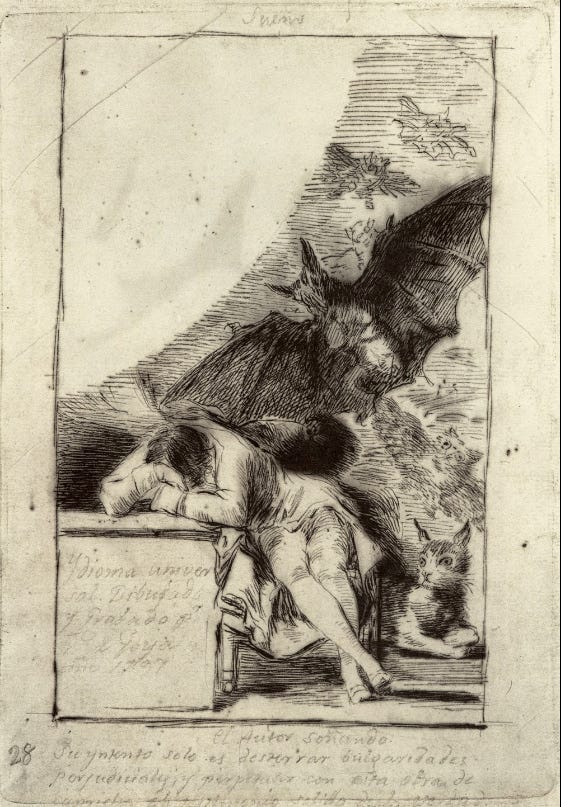

Before, fear would accompany such sensations. Fear of going blind. Fear of being touched. Now that he is blind, however, or at least purblind, he only fears the alien touch, being groped by strangers, by strange beings, putting his hands on decaying things or deformed things, things too repulsive to imagine: open sores, squirming eels and rats, insects that swarm, living things with slime for flesh or fly-blown flesh.

In others, it is ice again, all white, the pathway a narrowing chasm, giant dazzling cliffs that he is squeezed between, unbearably cold, his tongue frozen, unable to emit a sound.

When he finally pushes his way back into the outside, he usually sees shadows slinking through the rooms and down the corridors. But today the sun has annihilated every trace of his darkness; he sits insensible in its glare, exposed and outlined.

The afternoon becomes evening. The light slides away from the window. He drifts off. The lynx returns. The owls and bats descend once more from the dead trees on the hillside.

Is he feverish? The pestilence still assails his body and batters his soul. The last bout took most of his eyesight.

On the horizon now he sees the shadowed mountains. He remembers the cypress gardens and the olive groves on both sides of the road. He remembers the peasant’s round hats. He remembers their piety, their black cloaks and wooden clogs.

He remembers their carts, no more advanced than those of ancient Egypt, laden with maize or dung or the dead, the spokeless wheels – circles of wood with no axles – shrieking down pathways built not by men but by sheep and goats.

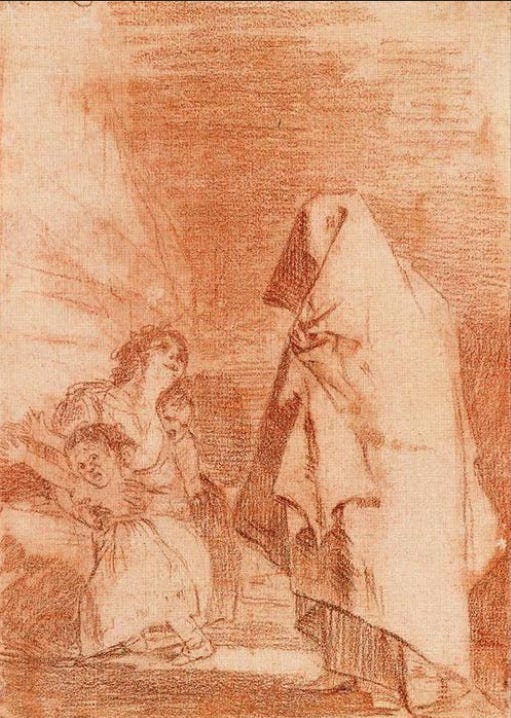

The peasants’ houses are filled with smoke and animals – sheep, pigs, and chickens that pay the peasants’ rent. Their houses are made of mud, they have no windows, chimneys or beds. The women trapped inside are veiled with white handkerchiefs. They have knives strapped to their thighs, sharp as Leocadia’s tongue.

He remembers the legs of the washerwomen on the sandbars along the banks of the Mansanares, not far from the farmhouse. The wet-nurses at the windows and on the benches in the park, las pasiegas, suckling the sick and the sickly, petticoats turned up over their heads like mantillas, phylacteries hanging from their waist.

He remembers, in the early days of the Riego revolt, when he and Leocadia watched a group of drunken young men near the Quinta throw three Franciscan friars into the river. They poisoned the fountain, a neighbour’s son told them. Probably the wells, too. The monks were weak swimmers or couldn’t swim because of the weight of their habits, which swirled thick and brown in the fast water around their tonsured heads and frantic paddling. They struggled comically to come to shore but the laughing young men pushed them back with sticks and threw rocks at their heads. They disappeared under the water, resurfaced, were hit with rocks, disappeared again. This went on for a few minutes. The lavandaras downstream folding up the day’s linens were doubled over with laughter. Two of the dead friars sunk. The third floated past the shrieking women. The men kept throwing stones, shouting with triumph every time one thudded into the already caved-in head.

He remembers the horse-market outside of Zaragoza, the dreary wastes and miserable villages, the sweet prospect of the city in the distance.

He remembers the bell of the church in Afilagro. The peasants say it contains a melted piece from the thirty received for the betrayal of our Lord. They say it tolls whenever calamities are about to befall. Once this happens, it cannot be stopped by human hands, only by God.

As the dreams and the remembering wane – the frame containing them disappear and the contents shake out into the awoken world – his breathing recovers and his body relaxes. A newly attuned focusing shifts to the details: the blur of the milkmaid on the landing wall, which Maguiro the banker wants to buy; the less hazy items on the desk; the sketchbook on his lap; the wide silk armrests of the chair, a Voltaire fauteuil with a violin back that he brought back from Paris four years ago, along with the extravagantly inlaid bonheur-du-jour that his head is resting on – a peace offering to Leocadia, livid because he did not take her on the trip as “tu verdadera y legítima esposa” – his true and legitimate wife – “which is what I have been for two decades.”

Leocadia hates the chair and desk because of their associations with his loathsome son and daughter-in-law, who would not allow her to go with him to Paris. Or perhaps because she finds them fussily modern and French. Which is why they are on the half landing of the grand staircase, far from visitors’ eyes.

He, however, who has used the chair and desk for the portraits of two bankers, a playwright, a painter and Brugada, his sometime assistant, finds their placement perfect; a comfortable way station in which to recuperate after each climb and descent, directly in front of a large oval window through which, if his eyes, clouded by cataracts, were not directed at the sketchbook on his lap, would allow him an unimpeded vision of the early afternoon sun on the cathedral’s twin spires, and, he imagines – he fully pictures this – the blue forested plains and low hills in the distance, the white villas on the yellow cliffs, the acacia hedges above, the trellised vines below.

The dead trees extend to the edge of what to him looks like a deep dark lake but is actually a wide river. Bordeaux lines the concave bank. The biggest port négrier in the world, slave built, slave fortuned. He imagines it on blackened ivory in miniature, viewed through the double loupe dangling from his neck, drops of water removing the black ground, the paint puddling, patches wiped with a cloth into shadows and highlights. The Gironde estuary in the background, and there on the wide, large-banked river the rolling bore of the tide moves towards him, advancing past the quarantine station, the water shining like silver plate, the wind rising, the flat, calm water stretched out behind the churn like a sheet of dark silk all the way to the first hesitant ripples on the Bay of Biscay.

Leocadia. In that dress. The light on her bare shoulders. The sheen of her skin. Ivory. Mother of pearl. Mother of God.

Seeing that she was descending the stairs in the pretty skirt from the dead queen, and that the sun had left the window above, he hoisted himself out of the chair, called out after her for his chocolate – and patted his pockets for a pencil.

Instead, what he found was a diminishing mirror, which he pulled from the pocket and held in both trembling hands as he paused, standing now at the top of the stairs, looking over his shoulder at the framed view of Bordeaux’s rooftops and the twin spires of the cathedral.

This is how it is used, backwards, facing away from what you wish to see reflected in the convex glass.

A Claude glass, that is the name for it, after the Frenchman whose works he had copied at eighteen in the Royal Collection at El Escorial. Perhaps for bullfights, he thought, composing the scene, flattening the tones, unifying form and line; but then he shook his head and abandoned the idea. The results were dingy, devoid of truth. Besides, his near-blindness already accomplished this trick.

He stepped back, peering through his double glass at the black mirror till he found the ideal image.

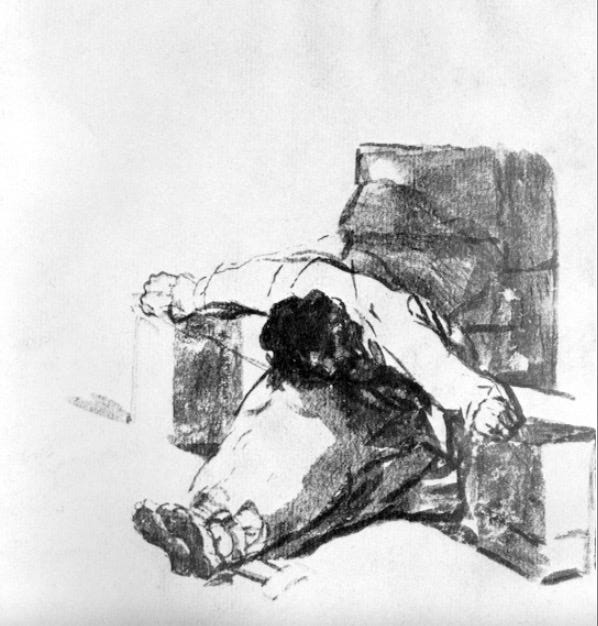

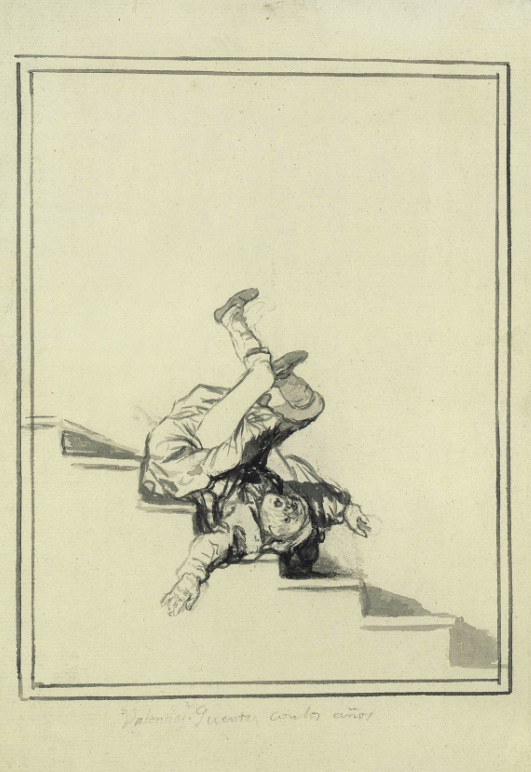

Then he fell down the stairs.

The terrifying cries of the owls and bats fill the air, wrest him from the deeper categories of sleep. Their wings pummel his face. The lynx appears next to the chair, its eyes shining in the dark. He calls out for help but no one hears him. Is he dead? Is everyone dead? Is the world dead?

What griefs attend that art. For the moment, however, which feels much longer, he is still on the landing and alive, and breathing, albeit shallowly, and snoring, and drooling, face down, his head – which he has always thought excessively large – resting heavily on the lady’s writing desk, a green and gold bonheur-du-jour that he purchased four years before on the rue Monnaie, at a marchand-mercier next to the porcelain shop of the Manufacture Royale de Sèvres.

This was on his only visit to Paris, during which he did dozens of sketches in and around his hotel on the rue Favart, mainly of prostitutes and amputees.

The prostitutes recently arrived from Aragón are gone, as is Leocadia, as are the owls, bats and cats, all gone, replaced by his mother. He asks her to tell him stories about the farm, about the animals, about the monks, about his grandparents. She cackles and flies away.

Near the end of her time on earth, she no longer recognized him, or could but only briefly, and when she could she would get angry, and then call him by the name of his father or one of his brothers, and say cruel things about him, how he didn’t care about her or anyone else, only himself and his accursed art. His so-called genius.

He had missed his father’s death but he was in the room for hers. One moment she was there, breathing quietly, and then, nothing, and then she cried out, “¡Nada!” and was gone.

Pepa’s departure was the same. He had taken her hand in his but she had pulled free. Then her breath calmed, and then it stopped.

He would like to sit down to a plate of oysters, and some criadillas, and then go to bed.

He produced only five easel paintings while in Paris: a savage bullfighting scene with thick black shadows and pooling masses of spilt blood; and four “primitive” portraits – the Marquesa de Pontejos, whom he had painted twice before in Madrid; Baron Dominique Vivant Denon, the former director of the Louvre and a pornographer; Javier Maria de Ferrer, an exiled Spanish banker and publisher; and Ferrer’s young wife, Manuela, whose Tuesday night tertulias in Paris were almost as lavish and well-attended as those the Marquesa de Pontejos hosted on Fridays.

He saw and admired paintings by Constable, Delacroix and Géricault at the Salon de Paris in the Louvre, and two that he detested by Ingres. He met the writer Stendhal, though they did not exchange words. He re-made the acquaintance of the Baron Denon, the Louvre’s director for whom, during the Peninsular War, he had compiled an inventory of artworks in the Royal collections for seizure and export to Napoleon’s new museum in Paris.

Throughout the Paris trip, which lasted six weeks, he was followed by secret agents of the Paris police.

“It would be interesting to verify whether, during his stay in Paris, he had suspicious dealings with any individuals which his employment in the Spanish Court would make even more inappropriate. Keep close tabs on him, by means of very careful and covert surveillance, and communicate the results to me, alerting me to the precise moment of his departure.”

Presumably beyond the ken of these observers, he spent an unchaperoned afternoon in a rented room of a boarding house on the rue Marivaux with the granddaughter of a farmer he knew from Fuendetodos, a washerwoman named Maria del Pilar and her two daughters, whom he rendered, three times, in pencil and red chalk, on antique Japanese laid paper given to him by a certain “Mister van den Hoogen,” a former lover of Leocadia.

He first noticed the police spies at the arcade, and again on the boat. Now, at the Louvre, he took Jéro’s arm and shuffled painfully into the next room, peering past the idle throng at the ho-hum muddle on the walls, no perceivable truth in any of it as far as he could see, which wasn’t far – only the pictures at eye level, and only these through the double loupe. Military portraits, cardinals, battles, mythical nonsense. A few genre pieces worth at best two minutes of reflection. English pastorals from Constable. Slumped, half-finished Greeks awaiting slavery and slaughter by Delacroix who, he was told, had purchased a set of his Caprichos; and an emboldened shipwreck by Géricault, who, he had just learned, died in January at the age of thirty-two.

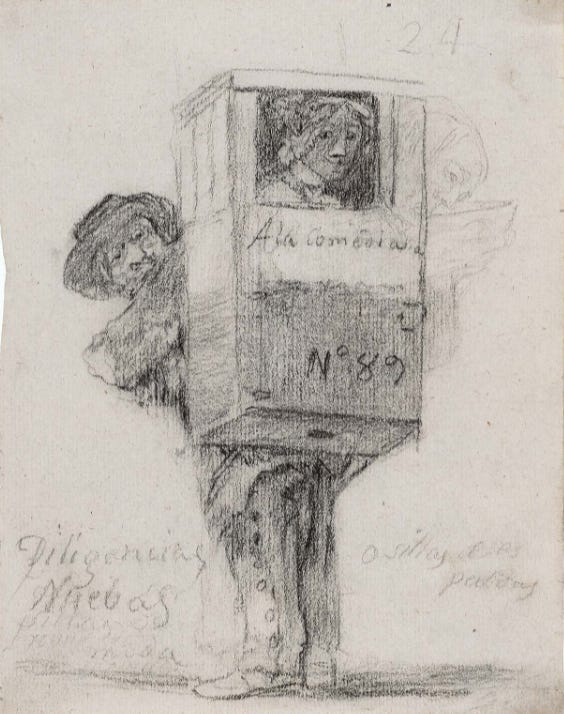

He tried to steady his brain, look for patterns, look past the patterns. Force his eye to stop its perpetual skid. Earlier that day, he saw and sketched an old woman with no teeth being wheeled down a street in a cart by a three-legged dog. The night before, he sketched the gas lights in the arcade, illuminating the goods and wares, including the strutting men and women – brightly coloured packages of seductive flesh.

Floating lavandarias on the river, two floors high, filled with washerwomen.

Men carrying women on their backs in brothel boxes.

He had no money left. How was this possible?

Vernet a possibility. His Bataille de Jemmapes had drawn the largest crowd. Or Granet. His cloddish cardinal, however, in front of him. What will he say? Nothing. Above it, a Jean d’Arc, and next to it more naked Romans marching off to war.

He suppressed a fart.

It is as if yesterday he stepped out into the night and walked into the darkness as young and strong as the god in the Jacques-Louis David painting before him, marching past the ravaged farms and the dead woods and the dry plains, walking until he can no longer recognise anything around him, including himself, or feel anything, including what it is like to be this strange old man who survived four kings and walked across two kingdoms and now, all these years and lives later, finds himself at the Louvre, at the opening of the Salon, the sun blazing on the white columns outside, feebly supported by a stick and the elbow of an unknown relative – the cousin of his daughter-in-law – exhausted and shivering in front of towering walls of terrible paintings, surrounded by peering monkeys brandishing ceremonial swords and smallpox scars.

His eyes are burning, his head is spinning. Is it fever? Typhus?

He scans the crowd with his good eye.

In his dress, as always, there has been no detectable forethought given to detail or style. Sturdy British boots instead of slippers, dark breeches instead of pantaloons, a striped silk waistcoat under a knee-length frock coat. The only concession to fashion is the wide cravat, tied in a soft bow, and the walking stick, black and ivory with an owl head in bronze, bought for him by Vernet this afternoon, after their tea in the Passage des Panoramas.

As always, too, he pretends to hear and understand everything that is said by the preening and fawning monkeys around him, taking his cue from their overplayed reactions, laughing at each witticism, nodding wisely at each sagesse. He is ever courtly in every address, smiling, bowing, standing when people leave, kissing the proffered hands of wives and mistresses, the rings of bankers, bishops and diplomats. But presently, he is kissed out, bowed into oblivion. It is far too hot for the pretence of manners and he is tired, and incontinent, and there are too many people, moustachioed apes and their preening mates gawking mindlessly at each other; and too much dreadful art, absurd statues crowding the floors, towering assemblages of gaudy tableaux on every wall. He has seen and not heard enough. He needs to sit but there is nowhere to sit. He puts more weight on the new stick and closes his eyes. The boy at his side, his nephew? The cousin of his son’s wife, is it Guillermo? Jéronimo. Jéro, who says something, shouts it at him with soured breath into a dead ear. What is there to say? He has seen and not heard enough and he is the oldest man in the room and it is time to go. The Ferrers are late, and he knows what Ferrer will say anyway, exactly what he said yesterday, that an audience is impossible, that the gouty king is half dead, that he has wet gangrene in his legs and dry gangrene in his spine. This is what was said yesterday, why would it change today?

At dinner with businessmen and spouses at the banker Laffitte’s hôtel particulier on rue d’Alfort, where he will be imprisoned for four hours between two monkeys at a long table piled with slathered food – why must there be abominable sauces with every dish in this country? Surrounded by mediocre paintings and plaster casts of Roman relics. He wants his portrait painted does our fat little Laffitte. A former clerk, now the patron of the largest bank in France. Formerly the Finance minister but, according to Ferrer, out of favour with the king because of his liberal largesse to Cadiz. Is that the true story? He has a letter of introduction from the King of Spain. Surely he can get an audience, if not with the obese king, then with his wife, or his son.

(The king has no son.)

Does he actually want it, though? Does he need it? He is tired. It is hot and there are too many people. The paintings are terrible and terrifying, mythic heroes and romantic claptrap pell-melled floor to ceiling. He wants to go home. Not home, back to rue Marivaux, to his window across from the theatre, where the putas travel in boxes on the backs of giants. But here comes Ferrer. Don Joaquin Maria Ferrer, who sat for his portrait last week, as did his wife, and who purchased his bullfight. Forty years old, half-length, standing and seen from three quarters in a black frock coat just like his, head turned from right to left, high forehead on a skinny face with cold eyes and a pointy nose and a tucked-in mouth under black hair cut “à la malcontent”.

Holding a book.

The wife, posed like him, but in a dark décolleté, shoulders covered with a folded down white collar, forehead framed by heavy black locks surmounted by some sort of fashionable bun. Full, sensuous lips, the neck bare. In her hand, the same red fan the prostitutes carry in the arcades.

The David is the biggest in the room. An absurd confection that he can’t take his eyes off. Its young naked god languorously sprawled out on the same sofa as in the Récamier, but suspended on a froth of clouds. Spear in one hand, sword in the other, with a pair of kissing doves to hide his cock and balls. Venus contorts near his lap, her hand on his thigh.

Ferrer tells him that the king is indisposed, but an audience will be held with the heir-apparent, Charles Philippe, Count of Artois.

What do the police want with him? He will not go see the lithograph exhibition. He will go another day with Vernet.

À l’enseigne du roi d’Espagne. That was the name of the shop where he bought the desk. He can still do this, pull things out, remember them. Not everything is forgotten. Hoogen’s eyes, for example. And Maria del Pilar. All the Maria del Pilars. He prides himself on this, always has. See something, store it away, retrieve it, reproduce it.

Of the spies, however, he has no recollection.

Around his neck, which he thinks little of, as it is not a pleasing match for the head, on a fine chain of Potosí silver, dangles the double loupe, a gift from the Younger Moratín, an old friend and the son of an even older friend, the Elder Moratín, with whom, in 1776, he collaborated on an illustrated edition of Arte de las putas (The Art of Whores), the circulation of which the Edict of the Inquisition of 1777 prohibited, which placed his name for the first time on the lista negra of the Holy Office.

If not for the intervention of Mengs, the First Painter to the King of Spain, this black mark would have cost him, then a thirty-year-old father of three (all died in infancy), his position in the painting studio of his brother-in-law, Francisco Bayeu, at the Royal Tapestry Factory in Madrid. He would have had to return to Aragon. To do what? Become a provincial church painter, wandering the countryside with his brushes and pots; or worse, a goldsmith like his father; or a farmer like his brother, back in Fuendetodos tending stunted and blasted crops, shovelling pig slop, making and selling blocks of ice for market stalls and rich men’s refreshment.

He will do more witches. He will do more birds. He will do mothers. He will illustrate Don Quixote. He will do men with goat feet. He will do Lot and his daughter naked and hideous, drinking wine, making love, the city of Sodom burning in the background. He will do the Song of Roland, the clear red blood running in streams on the green grass. He will do Queen Isabella and her armoured knights on horses, brandishing battle axes and lances, the severed heads of Moors swinging on strings from their saddle bags. He will do the mobs that followed them across the battle plains, the merchants who unburdened them of their spoils, the slave traders who bought their enslaved, the peasants who sold them food and the bodies of their wives and children.

Blacksmiths, tailors, tinkerers, beggars, pimps, whores, scribes, poets, musicians and players, following in carts and on foot through newly created deserts, knight-created. Everything they rode through destroyed, every crop trampled, every almond tree and olive grove cut down, every well plugged. Whatever they couldn’t carry away burned to the ground.

He will do the raiding parties; he will do the wild hill tribes that poached on strays too greedy to relinquish their plunder. He will do the Solano, the south-eastern wind that sweeps down those same hills, raising the temperature to a pitiless boil, and the stinging glare overhead and the deadly Siberian blasts that follow, ice-house air from snowy Guadarrama that rolls over the denuded plains and cannot extinguish a candle but will put out a man's life, pierce his bone to the marrow and bring in its wake consumption, pulmonia and the colico de Madrid, the illness that almost killed him fifteen years before. He remembers the metallic taste in his mouth, the black tongue, the heaviness in his bowels, the violent cramps, the bilious vomiting, the continuous and explosive farts. Cover your mouth, his mother would tell him when he was a boy in Aragon, and when he was a man in Madrid, cover your mouth and muffle yourself in your cloak, the assassin’s breath is blowing. The breath of death.

And the French, with their laughable courants d’air.

The peasants attributed Murat’s affliction to divine vengeance, but, Murat, unlike him, survived unfazed.

He was left deaf, half incapacitated.

Murat, who posed for him, became Marshal of the Empire and Admiral of France and the First Horseman of Europe. Two years later, for betraying his Emperor – he will draw this, he will paint this – after a long hot bath perfumed with the contents of a full bottle of eau-de-Cologne, he died, gloriously, by firing squad, shot through the heart twelve times by twelve of his own soldiers, his calm, piercing eyes ever upon theirs.

Murat did not accept a chair. He refused to be blindfolded.

“I have braved death too many times to fear it,” he said, standing erect and unintimidated; and after kissing the engraved cameo of his wife, he pushed his long black locks out of his eyes and said to his men, who were so emotional they could barely raise their eyes, let alone their rifles: “Soldiers! Do your duty. Straight to the heart and spare the face. Fire!”

He remembers meeting Murat with Baron Denon and General Soult in Madrid, and the sketches he made of them, and the portrait of Murat he later destroyed, and the brothel they visited in El Escorial, stocked with the mistresses of the Court, and the paintings he and Denon hand selected for shipment to Paris. The Madonnas of Murillo, the saints of Ribera and Zurbarán, the portraits of Velasquez. Paintings of Raphael, Michelangelo, Andrea del Sarto, Titian, Tintoretto, Paul, Veronese, Correggio, Domenichino, Guido Reni, Rubens, Van Dyck and Fra Angelico. Breughel, Teniers, Jordaens, Rubens, Durer, Schoen, Mengs, Rembrandt, Bosch, Joanes, Carbajal, Herrera, Luca Giordano, Carducci, Salvator Rosa, Menendez, Claude Lorain and Cano.

He remembers seeing French soldiers armed with hammers and saws descend upon a Gothic church in Torrijo, superbly decorated, with a fine facade, and strip it clean in an hour.

He remembers the Mudéjar interiors of the Duke and Duchess of Alba’s palace in Seville, yellow tiled floors, ironwork screens, honeycombed cornices, stucco friezes, timber beamed ceilings interlaced and delicately carved, which Napoleon’s army destroyed.

He remembers the palaces in Zaragoza, a city of palaces that the French forces ruined, and the beautiful convent of Santa Engracia that they sacked, and the splendid libraries, hospitals and churches that they gutted.

He remembers seeing the baggage train of the plunderers, some two thousand carriages long, filled with church plate, sculptures, paintings, delicacies, mistresses, poodles, parrots and monkeys – a half-mile long convoy of confiscated goods and animals, including eleven elephants and seven giraffes – most of it abandoned after Vitoria and repossessed by Wellington’s men.

His exile in France is self-imposed. His glowering portrait, painted a year ago by López, the king’s new favourite, hangs in the royal collection in Madrid. Were his legs not gone he would be free to come and go as he pleases; and he still paints and draws as he pleases; and if he leans in close the doubled spectacles, a gift from the banker Gallos, bring the perceivable world into workable view.

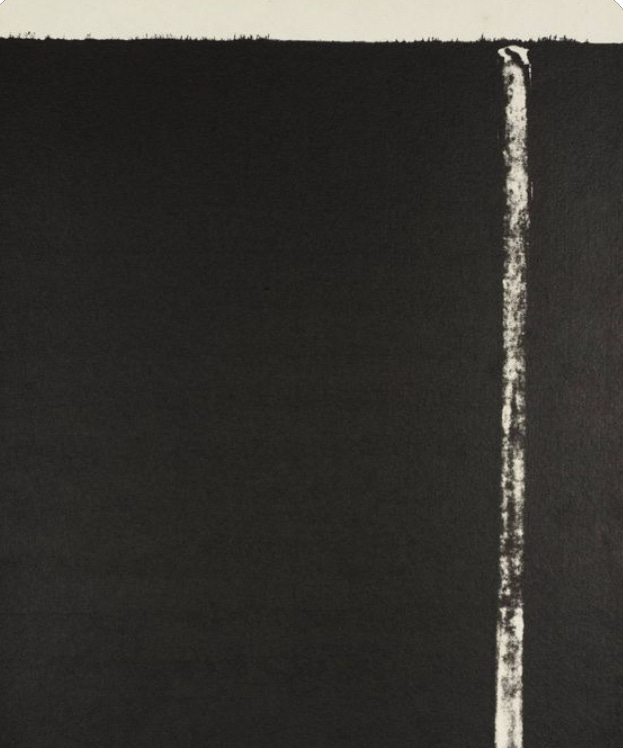

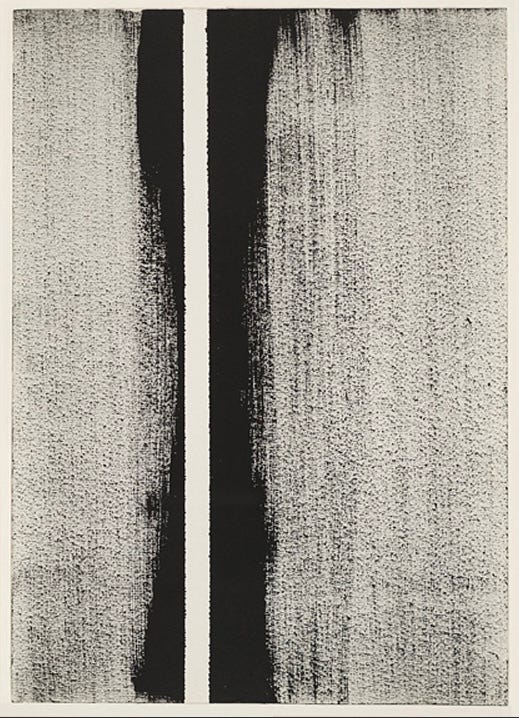

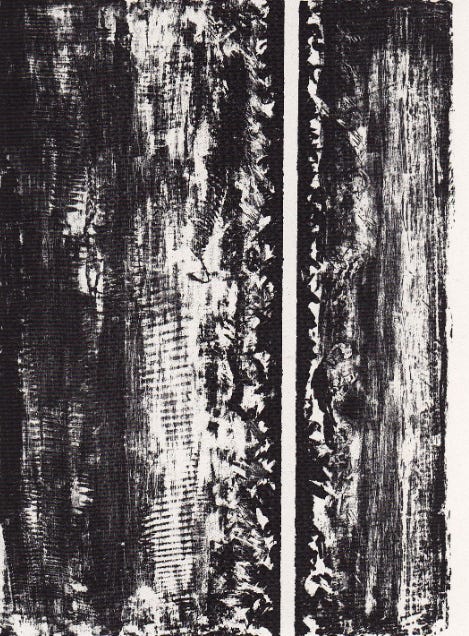

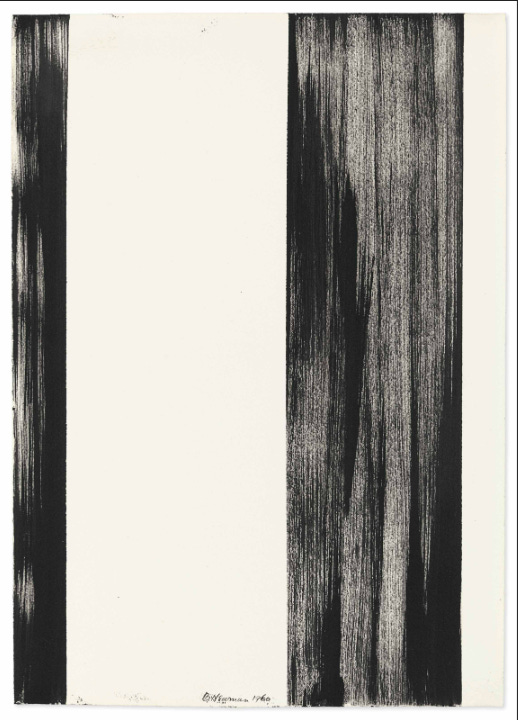

But he relies mainly on memory and imagination and accident: a puddle of water on a drop of paint, a drop of paint on a puddle of water. Nearer to the end, in just a few hours, he won’t be able to see, not even through a loupe, how the paint hits the canvas or pools in water on the miniature’s ivory, or how a murderous bull let loose in a panicking crowd emerges from scraped-away crayon on a lithographer’s stone. Gored through with cancer and poison, beset by aneurysmal strokes, he will soon be too frail to stand and pace at the easel.

However, it will be the fall that will dispatch him, less than an hour from now, a fall down a flight of stairs that will spare him his second childishness; and you too will spare him that indignity, and pose him here instead, on a page of his sketchbook, resurfacing from an afternoon nap and staring at his hand, which is stained with black crayon. Holding it close to his face, willing a tremor he can’t see to subside.

From The Inventions. Drawings, paintings and etchings by Goya (1746-1828), Newman (1905-1970) and David (1748-1825).