The Dream Hypotheses

“Dzh hrxs nrxsg hxsivryvn pzhhg, pzhhg hrxs nrxsg hxsivryvn.” – Ludwig Wittgenstein

Proposition

“One must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn't going to go off.” – Anton Chekhov

Doves and pigeons abound in and around Paris and have for more than a century; but their numbers have doubled in the last fifty years. This is true in many large metropolitan areas. Cities aren’t as cold as the countryside, or so it seems to humans and birds, and there is more food and fewer predators. I, however, predate birds. This doesn’t mean I am older than birds – they go back to the dinosaurs, which evolved “flight ready” brainpower well before they actually took to the air. No, I mean I eat birds. Store-bought chicken, turkeys, capons and quails for the most part, pigeons and geese – and ducks, too, though their numbers have been of late most decimated by toxins, botulism mainly, which grows in mud warmed by unseasonably hot sun. I don’t bother with cormorants because of their fishy diet and because I find the flesh unpalatable, like eating rubber bands, and because of their appearance, and, especially, their character, which I admire. Seagulls are nutritious and low in cholesterol and fat, but the meat is unpleasant. Canada geese are repellent. I say this though I too am Canadian. They carry diseases. They beg and stalk. Their droppings are toxic.

Proposition

“Take off that wig or I will knock it off.” – G.K. Chesterton

On the last page of his last notebook, Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote, less than two days before his death: “If someone believes that he has flown from America to England in the last few days, then, I believe, he cannot be making a mistake. And just the same if someone says that he is at this moment sitting at a desk & writing. ‘But even if in such cases I can't be mistaken, isn't it possible that I am drugged?’”

If I am, and if the drug has taken away my consciousness, then I am not now really talking and thinking. I cannot seriously suppose that I am at this moment dreaming. Someone who, dreaming, says “I am dreaming”, even if he speaks out loud when doing so, is no more right than if he said in his dream “it is raining”, when it is in fact raining. Even if his dream is actually connected with the noise of the rain.”

The above was not written in Wittgenstein’s Geheimschrift cipher code, as many of Wittgenstein’s diary entries were, dating back to the earliest entries, when he was a voluntary artillery gunner on the Goplana, a gunboat captured from the Russians on the Vistula. Even the famous “Whereof one cannot write, one must not write” was originally written, as in my subtitle, as “Dzh hrxs nrxsg hxsivryvn pzhhg, pzhhg hrxs nrxsg hxsivryvn.”

In Tractatus, “Dzh hrxs nrxsg hxsivryvn pzhhg, pzhhg hrxs nrxsg hxsivryvn became “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” Or, as Wittgenstein’s friend and translator, Frank Ramsey put it, “What we can't say we can't say, and we can't whistle it either.”

Writing, saying, whistling. Thinking. Everything that can be thought at all can be thought clearly. Everything that can be said can be said clearly. The Geheimschrift cipher is uncomplicated. A child can crack it. Why then did Wittgenstein use it? Why ineffectually hide one’s secrets? Hide them, or barely hide them, pretend to hide them, from who, from what?

Proposition

“I remember that when I spoke to Nietzsche for the first time – it was on a spring day in St Peter's Basilica in Rome – during the first few minutes I was surprised and deceived by his elegance and sophistication. But I was not taken in for long by this lonely man, who wore his mask as awkwardly as someone who has come out of the wilderness and mountains dressed in conventional clothing; very soon the question arose, which he himself summed up in the words: “Whenever a person permits something to become visible, one can ask: what is it supposed to hide? What is it supposed to distract the eye from? What prejudice should it arouse? And then: how far does the subtlety of this disguise go? And in doing so, what is he getting away with?” – Lou Andreas-Salomé

The questions raised above by Nietzsche rise again and again. Quoting is a type of wig wearing. A hiding, a disguising. Our worst concession, he warned, our most dangerous betrayal, is to see ourselves as depositories of the thoughts of other thinkers, which we can call up – “regurgitate” – on demand. “Think for yourself,” he often said. “Use your own words.”

Proposition

“Is it the vague rumours of the reeds, the strange phosphorescence, the deep silence enveloping them in the calm of night, the bizarre mists trailing over the rushes like dead women's dresses, or the imperceptible lapping, so light, so soft, and more terrifying sometimes than the cannon of men or the sky’s thunder, which makes the marshes look like dreamlands, like dreadful countries hiding an unknowable and dangerous secret? – Guy de Maupassant

The passage about the marshes cited above is from a Maupassant story first published in Gil Blas in 1886. In the first paragraph, the narrator describes reading a fait divers in a newspaper:

A drama of passion. He killed her and then he killed himself, so he must have loved her. What matters He or She? Their love alone matters to me; and it does not interest me because it moves me or astonishes me, or because it softens me or makes me think, but because it recalls to my mind a remembrance of my youth, a strange recollection of a hunting adventure where Love appeared to me, as the Cross appeared to the early Christians, in the midst of the heavens.

The narrator then describes a duck hunt he attended with his cousin (“gentilhomme de campagne, demi-brute amiable”) on the marshes at daybreak. After he shoots a female teal, its heartbroken mate continues to circle overhead, unable to leave his dead love, whose bloodied corpse the narrator holds in his hands.

“You have killed the duck,” says the cousin, “and the drake will not fly away. Leave her on the ground, he will come closer soon enough.”

And he did indeed come near us, careless of danger, infatuated by his animal love, by his affection for his mate, which I had just killed. Karl fired, and it was as if somebody had cut the string which held the bird suspended. I saw something black descend, and I heard the noise of a fall among the rushes. And Pierrot brought it to me. I put them – they were already cold – into the same game-bag, and I returned to Paris the same evening.

I loved the ocean as a child. But it is too grand for me now, too unfathomable. As are rivers, with their unseen currents. I knew a fisherman who pulled two dozen corpses from the Fraser in his lifetime. The fen, the bog, is just the right size to seize and hold my imagination. Maupassant understood this. All bodies of water brought forth in him a tumultuous passion, but especially the swamp, which is an “entire world, a different world”, with its own forms of life:

For is it not in these stagnant and muddy waters, in the heavy dampness of drenched earth warmed by the heat of the sun, that the first seed of life stirred, and vibrated, and opened itself to the day?

This dead water, where unseen existences palpitate and thrive, this is my new world.

Proposition

We must admit that the divine banquet of the brain was, and still is, a feast with dishes that remain elusive in the blending, and with sauces whose ingredients are even now a secret. – Macdonald Critchley

It has been suggested that music triggered in Freud a form of reflex epilepsy. Members of his household said that when he heard music, he put his hands over his ears. He did not allow it to be played in his home. He forbade his children to learn instruments.

In 1937, two years before Freud’s death, the British neurologist Macdonald Critchley, who famously called psychoanalysis “the treatment of the id by the odd”, coined the name of this condition, “musicogenic epilepsy”. Those so inflicted cannot listen, think about or play music with “emotional content” without precipitating focal seizures.

Did Dr Freud suffer from this condition? Was he melophobic? As far as I can ascertain, he only wrote about music twice:

In The Psychopathology of Everyday Life:

Whoever takes the trouble, as Jung (1907) and Maeder (1909) have done, to pay attention to the tunes one finds oneself humming aimlessly and unconsciously, will regularly discover the relation between the lyrics of the melody and the subject preoccupying the person humming it.

In The Moses of Michelangelo:

With music, I am almost incapable of obtaining any pleasure. Some rationalistic, or perhaps analytic, turn of mind in me rebels against being moved by a thing without knowing why I am thus affected and what it is that affects me. This has brought me to recognise the apparently paradoxical fact that precisely some of the grandest and most overwhelming creations of art are still unsolved riddles to our understanding.

Proposition

It is the eyes of others and not our own eyes which ruin us. If all the world were blind except myself I should not care for fine clothes or furniture. – P.T. Barnum

I’m thinking of this now because one drunken afternoon in January 1995, a group of us were listening to a friend sing on a rooftop in the Fifth Arrondissement, on the rue Monge, just up from the river. The friend, now dead, was a baritone. He had performed in all the major opera houses of the world.

We were attending a birthday party in the seventh-floor chambre de bonne of a friend whose name I have forgotten. Actually, we were celebrating several birthdays: mine; my brother’s (who wasn’t there; we phoned him while the host was out getting ice on the rue Anglais); a young woman from New York named Sara Tanis Leopold; and a French girl from Arras who I didn’t know. The host was a non-smoker, which was why we were on his roof; there was a trap door in the ceiling of the hallway just outside his front door, with a drop-down ladder, which we had climbed up and out onto the roof, leaving behind our host and two young French women, a second girl from Arras and another from somewhere else, both students at the Sorbonne, which was just up the hill from the apartment building.

There once was a lass from Arras…

Most of these people were and still are my friends. Others, the French women, a perfumer from Grasse named Pierre, a mathematician from Dublin, I met that day and never saw again. Later, I had a falling out with Sara. Others have drifted away or, like the baritone, are dead.

The ugly tower of Église Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet dominated the immediate foreground.

We could hear the church’s organ, “Après un rêve”, Gabriel Fauré, and when it finished, over the car traffic and the jackhammers, the amplified voice of its excommunicated priest performing the Tridentine mass in Latin.

Proposition

Society must go on, I suppose, and society can only exist if the normal, if the virtuous, and the slightly deceitful flourish, and if the passionate, the headstrong, and the too-truthful are condemned to suicide and to madness. – Ford Madox Ford

In 1890, when he was still a young man, in Paris studying hysteria and hypnosis with Professor Charcot, Freud let the professor’s wife convince him to go to the Eldorado, a café-club in Montmartre, where he heard the French singer and actress Yvette Guilbert. Guilbert had been the fétiche model of the Toulouse-Lautrec. He drew her hundreds of times, emphasising her slim waist, dark, soulful eyes, and long black gloves.

Freud heard Guibert sing “La Soûlarde”, which made him “shudder’. Then she sang “Dites-moi si je suis belle” (“Tell Me that I’m Beautiful”), which made him whisper, “Yes, with all my senses.”

Smitten, Freud went backstage. He and Guilbert became friends. We are unclear what form the friendship took in its earliest stages, but later they exchanged letters, and Freud hung a signed photo of Guilbert over his desk in his study in Vienna, next to photographs of Lou Andreas-Salomé and Marie Bonaparte, and again on the wall of his Maresfield Gardens study, during the last year of his life in London.

Proposition

“The mind is a scoundrel.” – Fyodor Dostoevsky

The men playing speed chess in the garden were in their 40s. One wore camouflage clothing and a cloth cap. The other had a moustache and dark-blue eyes. He, someone watching whispered, had handily won his last six matches against different opponents, all of whom, the vanquished, were still standing around the table, eager to see the victor devour his next prey. Among them were two North Americans. One was lean and bearded, around 50 years old. The other was younger. They asked each other questions, but neither seemed interested in the other’s answers. The lean one was an investor. Cryptocurrency. The other was living on his parents’ money. Was one of them conning the other? Which one?

The man in the camouflage clothing ran out of time on the clock. The man with the moustache politely showed him the mistakes he had made. The defeated man thanked him and gave his seat to the younger North American, who took the black pieces and deliberated for almost half a minute before making his first move.

Proposition

When I first started jotting down ideas and thoughts, phrases like these or just individual words, whatever came into my head, I took inspiration from Anne Frank, Helen Keller, Virginia Woolf, and of course Samuel Pepys, as he started his diary when he was 27, the same age I was at the time I started mine.

For me, at this period of my life, the ever-present diary, like the accompanying pen, the pastis, the cigarette, was a talisman, a ceremonial object. And a voice I could trust and confide in. And something to make me appear engaged and interesting. This of course was before I could see Samuel Pepys for what he truly was: a violent, predatory male, a serial sex offender, a groper, a voyeur, a stalker and a rapist.

Proposition

Just after Vatican II, the priest’s predecessor had burst into the church with a group of followers in the middle of Sunday evening service and thrown the previous priest and all his attendants and parishioners out on the street. The church was then taken over by the Society of Pious X. Most of its parishioners were members of the far-right party, the National Front. After mass, they would congregate in front of the ugly church (which had been designed by Charles Le Brun), smiling and chatting, admiring each other’s infants, discussing childcare and the relative merits of their top-of-the-line strollers. They looked like everyone else; this is what struck me; there were no skinheads. They were normal-looking people.

The following year, the priest performed a Tridentine Requiem Mass for the soul of the Nazi collaborator Paul Touvier, the only French person ever convicted of crimes against humanity.

Proposition

He had always mostly liked his city, when he was in it, when the temperatures were right and the jackhammers not in his ear. He was especially fond of it now, early May, a sizeable swath of the functioning populace out of town for the school holidays, those visibly remaining, the able-bodied, the homeless, the tourists and the poor spilled out in random configurations, standing alone or in groups, sitting on the river’s edge and at tables on the terraces, drinking and eating, smoking cigarettes stuffed with hashish, talking together or to themselves or on their phones.

On his unfolded bike down past the new baker, the road crew and the restaurant recently converted into a design studio. Down past the east and south walls of the hospital, past the intersection where, a few years before, gunmen killed a dozen people. Then, the flush beginning to fade, across the water to the big square with the giant statue.

Proposition

In a diary entry from the early 1950s, Wittgenstein speculates about using a pressure gauge, a manometer, like those in the Voight-Kampff machine, to indicate changes in his blood pressure (or his pulse) resulting from a sensation he experiences; and then he describes how he could then write the sign “S” (for “Sensation”) in his diary (or his calendar) every time he experiences the sensation, and then verify it against the manometer, to see if his blood pressure went up. When there was a correlation, he could place a tick next to the entry. And this correlation would show “S” is “approved” by the manometer. But not that there is any correlation between the sensation and the word “S,” or between the sensation S and the manometer’s blood pressure reading.

This is my experience… And it appears entirely unimportant whether or not I have correctly identified the sensation. Let’s assume, I am constantly wrong about the identification, it wouldn’t make a difference. And that in itself is a sign that the assumption of this mistake was an illusion. (We flip a switch, as it were, that looked as if it would serve to adjust something on the machine, but it was simply there for decoration and not at all connected to the mechanism [my emphasis]). And what reason do we have here, to call “S” the symbol of a sensation? Perhaps the way in which this symbol is used in this language-game. – And why a “particular sensation,” the same one every time? Well, we assume this, we write “S” every time.”

Flipping the switch. The beginning of our lives is spent watching the world and learning how to talk about it, and to it, and, especially, how to talk to oneself, how to split oneself in two, confront oneself, oppose oneself to oneself, and question oneself, put pressure on oneself, make demands on oneself, persuade oneself. Later, nearer the end, we try to put those two parts back together again and heal the rift.

Am I hiding things here? Nothing of interest. But if I were, they would remain hidden.

Proposition

In 1931, in a response to a theory of acting and the performing self that Louise Guilbert proposed, Freud wrote:

The idea of abandoning one's own personality and replacing it with an imaginary one has never completely satisfied me. I rather suppose that there must be an opposite mechanism. The personality of the artist is not eliminated, but certain elements, for example, predispositions that have not managed to develop or repressed motions of desire, are used to compose the chosen character and thus manage to express themselves and give it a character of authenticity. This is much less simple than the ‘transparency’ of the self that you put forward. I would naturally be very curious to know if you can detect any traces of this other state of affairs. In any case, it is only a contribution to solving the following beautiful mystery: why does one shudder when hearing La Soûlarde, or why does one answer ‘yes’ with all one's senses to the question: ‘Tell me if I am beautiful’, but one knows so little about it?

By this I think Dr Freud meant that he didn’t think that an actor should completely forget their own personality and pretend to be someone else, but should use some parts of their own personality, such as hidden feelings or unrealised potentials, to create the character they are playing. This way, the character becomes more realistic and expressive. This is more complicated than the idea of “transparency” – a “blank slate”. “I wonder,” Freud seems to be asking, “if you can notice any signs of this process in my work?”

Anyway, this is how I try to explain the following mystery: why do you feel a chill when you hear La Soûlarde, or why do you say ‘yes’ with all your senses to the question: ‘Tell me if I am beautiful”, but you don’t really know why?’

Guilbert rejected this: “No, I don't believe that what comes out of me on stage is a ‘surplus’ that is removed and then used. I could be the Tzarina, the Tzar, Saint Francis of Assisi if a text is given to me to express them, I would feel the physical side of it, by the habit of transporting from my brain to my flesh.”

Proposition

I am a golem, I have no soul. Everything near me lives, everything has a soul, their souls send out long, narrow, pointed threads, rays that come to me, penetrate me, stir me, force me to my feet, order me to move, act, run. But I – I myself am nothing! Who then does the thinking? What within me thinks? Again, a stranger? Not me. – I. L. Peretz

I. L. Peretz’s most famous story was “The Golem’, which starts with this sentence: “Great men were once capable of great miracles.” It then describes the pogrom in the ghetto of Prague, during which certain Gentiles sought to “rape the women, roast the children, and slaughter everyone.” When it looked like the end was near and all hope lost, Rabbi Loew took his nose out of his Talmud, went into the street, walked up to a clump of clay in front of the schoolteacher’s house and moulded it into the shape of a man. He blew into its nostrils, and when it came to life, whispered the Name in its ear, and up the golem got, and out of the ghetto it strode. The rabbi resumed his reading, and the golem attacked the gentiles, thrashing them as if with whips. They fell like flies and the city filled with their corpses. “Rabbi,” pleaded the head of the ghetto, “the golem has hacked up all of Prague! Soon there won’t be a gentile left to light the Sabbath fires or take down the Sabbath lamps.”

Once more the rabbi put down his book. He went to the altar and recited the Song of the Sabbath. The golem stopped, returned to the ghetto, entered the House of Prayer and stood before the rabbi, who whispered something in its ear. The eyes of the golem closed, the soul fled its body, and it became once more a golem of clay.

Proposition

Listening to Mr. Mitterrand I am reminded of the verses of the poet Charles Perrault, parodying Virgil, describing Aeneas’s descent to the underworld: “I saw the shadow of a coachman / Who, holding the shadow of a brush / Was cleaning the shadow of a carriage.” It seems to me that today's dialogue belongs to a literary genre that rhetoric teachers have long loved: the dialogue of the dead. – Georges Pompidou

To the west, the two towers and spire of Notre-Dame-de-Paris commanded the view. In less than a month the funeral of the President Mitterrand would be held there, with Barbara Hendricks singing Fauré’s Requiem, the Chiracs in the front row, Fidel Castro behind, next to Prince Charles, next to Helmut Kohl, next to Prince Ranier; and further back the spire of Saint-Chappelle, home to fragments of the Cross, the Lance and the Sponge. Saint-Eustache beyond to the left, the Pompidou Centre behind that to the right, Sacré-Coeur up on the hill; and closer, almost below, the rue de Bièvre, which is where Dante once lived, and at that time was where the Mitterrands were living, at No. 22, in an ancient relais de poste with an inner courtyard hidden behind green doors.

Proposition

On the day that Dr Freud penned his letter to Guilbert, he had his first meeting with his personal physician, Max Schur, during which he made him promise that “when the time comes,” he wouldn’t let the medical establishment “torment” him unnecessarily. Ten years later, in 1939, as Freud approached death from cancer, he reminded Schur of his promise. Schur patted his hand and said he would administer the necessary sedation. On that same day, Virginia and Leonard Woolf visited Freud in his Maresfield Gardens house. Leonard found him to be “extraordinarily courteous in a formal, old-fashioned way – for instance, almost ceremoniously he presented Virginia with a flower. There was something about him as of a half-extinct volcano, something sombre, suppressed, reserved. He gave me the feeling which only a very few people whom I have met gave me, a feeling of great gentleness, but behind the gentleness, great strength.”

That night, Virginia wrote in her diary:

Sunday 29 January 1939

Dr Freud gave me a narcissus. Was sitting in a great library with little statues at a large scrupulously tidy shiny table. We like patients on chairs. A screwed-up shrunk very old man: with monkey’s light eyes, paralysed, spasmodic movements, inarticulate but alert… immense potential, I mean an old fire now flickering.

Proposition

A dream or nightmare is really only like a film inside your gulliver, except that it is as though you could walk into it and be part of it. And this is what happened to me. It was a nightmare of one of the bits of film they showed me near the end of the afternoon like session, all of smecking malchicks doing the ultra-violent on a young ptitsa who was creeching away in her red red krovvy, her platties all razrezzed real horrorshow. – Anthony Burgess

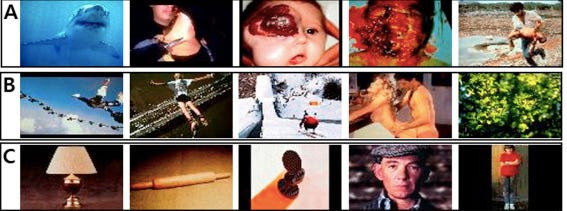

Clockwork Orange introduced readers and viewers to the Ludovic Technique, a Pavlov-inspired aversion therapy designed to reduce violent crime and prison overcrowding by making the visual appearance of violence physically and mentally unbearable. It did this by strapping the subject to a chair; injecting the subject with a cocktail of fear/vomit/paralysis-inducing drugs; forcing the subject’s eyes open with metal specula; and projecting moving images of violence – World War II footage, rapes, beatings, bludgeonings, murders, animal slaughter – which the subject has no choice but to watch.

The method was approved for trials by the UK Minister of the Interior. It was performed at the State Institute for Reclamation of Criminal Types in Uxbridge by Dr Brodsky of the Ludovico medical facility.

Today, most psychophysiological measurements (brain imagery, skin conductance, heart rate, fMRI, EEG, and electromyography) record valence, arousal and dominance responses to the colour photographs in the International Affective Picture System (IAPS).

The IAPS’s 956 images are also used to induce and influence anxiety and negative affect.

Proposition

Freud was inarticulate because he had inoperable cancer of the jaw. A giant suppurating tumour in the mouth, black as a meteorite and shaped like a star. Eating his flesh and bone. He had to wear a special prosthesis to keep his oral and nasal cavities separate. He couldn’t eat, couldn’t talk, and the necrotic bone stench kept his beloved dog, Lun, a red chow, from coming anywhere near him; it would howl if Freud’s daughter, Anna Freud, forced it into the study; so Freud sat by himself at his writing desk, or covered in blankets and rugs on his psychoanalyst’s couch, surrounded by his treasured antiquities, including the urn that he and his wife Martha’s ashes would later be sealed in, writing about how the Hebrew prophet and lawgiver Moses was an Egyptian, how he created the Jews, and how they turned on him and killed him because of the harsh laws he had imposed upon them, especially the obligation to love and fear an invisible God and the prohibition against making an image of that God – “the compulsion to worship a God whom one cannot see” – which in turn lead to their “triumph of intellectuality over sensuality” and their ability to excel in law, mathematics, science and literature. And, of course, music.

Proposition

“The cataclysm doesn’t happen, we don’t do any of it, because we find ourselves back in the heart of normal life, where negligence deadens desire. And yet we shouldn’t have needed the cataclysm to love life today. It would have been enough to think that we are humans, and that death may come this evening.” – Marcel Proust

My attentions, however, were solely on my breath, which would have been invisible but for the smoke from my cigarette. And it should have been visible, every huff and puff, as it was winter and sunny and very, very cold. Why, I said out loud, can’t we see our breath? “Because of relative humidity,” said one of the young French woman from Arras. She was wearing a thick down jacket. No one else had brought a coat. “L'air est insaturé,” she said. “Comment dit ça?”

“Unsaturated.”

“Like the fat?”

“The air can hold more water vapour.”

Her name was Valerie. She was doing a Masters in Material and Structural Mechanics at the Ecole Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, which back then was still on the rue des Saints-Pères in the Sixth Arrondissement.

Proposition

Marie Bonaparte was the great-granddaughter of the French emperor Napoleon I, and the author The Life and Works of Edgar Allan Poe: A Psycho-analytic Interpretation. She is best known, however, for the papers she published on female sexual pleasure under the pseudonym A. E. Narjani. This involved research in which she measured the distance between the underside of the clitoral glans and the centre of the urethral meatus in 243 women. She found that the distance determined a woman’s ability to achieve pleasure (volupté) and reach vaginal orgasm during missionary position coitus. She paid a Viennese gynaecologist named Josef Halban to move her clitoris closer (rapproché) to the urethral passage by severing of the suspensory ligament attaching it to the mons pubis. The 20-minute procedure, called a Halban-Narjani operation, did not work. Halban performed it a second time. And a third. Freud disapproved.

Proposition

Max Schur kept his promise. On September 23, 1939, Freud went into a morphine-induced coma and never re-emerged. He was 83 years old.

Proposition

Mitterrand, who had left office on May 17th, after 14 years as President of the Republic, was still alive – he died, or rather was killed, by lethal injection, a month later – but not living in the house on Bièvre, except on Sundays, when he had dinner with members of his first family. He and the dog had been living, since leaving Elysée Palace, on the third floor of 9, avenue Frédéric-le Play, in the Eighth Arrondissement, in an apartment that the French state had put at his disposition.

The lethal injection was administered by Dr Jean-Pierre Tarot, an anaesthesiologist specialized in pain management. Tarot had left his practice two years before and had been at the President’s side since. They had met through a mutual friend, Jean Riboud, the chairman of Schlumberger, who, had been incarcerated in Buchenwald, the Nazi concentration camp, for two years – when he was liberated, he had tuberculosis and weighed 98 pounds.

When Riboud was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 1985, he relinquished control of Schlumberger, which at the time was the biggest offshore oil drilling company in the world, and put Dr Tarot on a full-time retainer, to manage his pain and see him through his final days.

The President remembering this – he thought about Riboud, and a handful of other departed friends, daily – did the same. And when he relinquished control of the nation, at the time ranked third in the world for GDP, he told the French people during a televised speech, “I believe in les forces de I’esprit (“the forces of the spirit”) and I will not leave you.” Later, he told Patrick B., that he was “not afraid of being dead, but of no longer being alive.”

Proposition

Few people can be as tortured by writing as I am. – Virginia Woolf

I have yet to try swan. They were once the favoured dish of the Kings and Queens of England. I killed one once, by accident, while riding a bicycle drunk. I swim twice a week in the canal, and male swans often chase me away from their nests, wings opened, hissing like a thousand snakes, ready to strike. I find them humorous.

Proposition

Freud’s urn, a gift from Marie Bonaparte, is a 4th century BC bell krater, used to hold wine for drinking parties. The bearded figure with the vine and ivy-covered staff, a giant fennel stalk topped with a pinecone – a thyrsus – and the high-handled drinking cup – a kantharos – is probably Dionysus, the god of wine, madness, masks and death. He is gazing longingly at one of his female followers, a naked maenad carrying a wine jug and a lit torch. It is night. Everything beyond the throw of the torchlight is pitch black. A naked young man holds another drinking cup with both hands. A satyr playing a double flute leads the rest of the procession, which includes two cloaked initiates that look like they are about to set off on a journey – on the column between them it says termon, which means both “beginning” and “end’.

Proposition

His head and mine were both bending over the bald head of the wigless Duke. Then the silence was snapped by the librarian exclaiming: “What can it mean? Why, the man had nothing to hide. His ears are just like everybody else’s.” “Yes,” said Father Brown, “that is what he had to hide.” – G.K. Chesterton

Danielle had left her bedside vigil the night before, around 7pm, when the President, dressed head to toe in black, told her it was time for her to go, that he wished to meet death fully conscious and fully alone, except for his administering angel, Tarot.

The next morning, upon hearing that Yasser Arafat was on his way up to the third floor to pay his last respects to the President, Danielle cancelled her own deathbed visit, just as she was about to turn the knob and enter the apartment. Why? she asked herself. To what end? What did she need to see, to do, to say? There is nothing more to say. And then the door to the apartment opened, and she was told that Arafat was in the elevator, on his way up. She and Baltique immediately took the stairs, a GSPR man carried Baltique – the dog’s hips were too arthritic to climb down on her own. Together they returned to rue de Bièvre in a limousine driven by a Patrick B., a member of the security team. There were Christmas lights on in the shops. On that street alone, three people had already thrown away their trees.

Patrick B. opened the gate with a remote-control device on the hinged visor above the windshield. The car drove through the gate entrance and parked in the courtyard. We saw all this from the rooftop.

Arafat, meanwhile, beside himself with grief, fell onto the corpse of the President, crying uncontrollably. Someone else – to this day we still do not know who – surreptitiously took a photograph of the President on his death bed. The following week, the photo appeared in the pages of Paris Match, accompanied by a story about Le Grand Secret, a book published that same day by Editions Plon, and written by Mitterrand’s personal doctor, Claude Gubler, who had been dismissed a few months earlier, during a bitter battle between the President’s different doctors for control of the President’s medical treatment. Because of the book, he had his license revoked and was forced to close his practice.

Proposition

We were enjoying the way the clouds of smoke and air vapour intermingled and climbed into the sky – at least this is what we thought we were enjoying, as it was cold that night. The angle of the roof was such that no step felt safe, the zinc was slippery, but just the same I had managed to coax the group, who, collectively, were afraid of heights, and shivering almost uncontrollably because of the cold, to make their way together over to the north-western corner of the building, right to the very edge. There was no railing to hold onto. The view of the full northern span of the city stretched out before us, starting directly next door with the ugly tower of Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet. I pointed out the Mitterrand house. There were two men at two of the four windows on the top floor. A third man was standing motionless in the courtyard. All three were wearing dark sunglasses.

We heard barking. Something bright caught the light and shone into my eyes, then Sara’s, and then Pierre’s, the perfumer.

“Is that a gun?”

Sure enough, the barrel and scope of a rifle could be seen at one of the windows on the top floor of the Mitterrand house. Valerie gasped. Baltique was still barking. I had heard her loud bark many times before, every time that I visited my friend’s apartment. In fact, it was so loud that, after the President’s funeral, and the reading of his will, which made no mention of Baltique, no one in the President’s two families wanted to take him in. She ended up in the care of Patrick B., with whom she happily lived, first in Satory, near the military barracks, and then in the Marne.

Proposition

“For an answer which cannot be expressed the question too cannot be expressed. The riddle does not exist. If a question can be put at all, then it can also be answered.” – Ludwig Wittgenstein

Hexigon is quickly becoming my favourite - and the highlight of the day of the week I set aside for my self

I read Hexagon and am (mostly) reassured that the chatbots can never replace human intelligence.