A surplus of particles and a deficit of awareness

Anosognosia and the air we breathe: a deadly combination

Every morning last week I woke with a headache and a cough, and a somewhat green and grotty feeling at the back of my throat.

The cough nagged at me all day.

I sneezed a lot.

Covid?

Last week, too, like most weeks, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets of Paris, motivated by what they viewed as causes of grave urgency.

On Monday, there was a support rally for three Lycée Racine students who the week before had been tear-gassed, beaten and taken into custody for picketing. Participating in these blocus pickets, long seen as a rite of passage for high-school students – an essential part of their political education – last year became illegal, punishable by very stiff fines and prison sentences. The three Racine students, all minors, go on trial in April.

On Tuesday, teachers, parents, students, union representatives and elected officials demonstrated in front of the Paris rectorate on the Rue des Écoles against the closure of classes. Also demonstrating that day, and for the second time in a week, were doctors – general practitioners and specialists – who marched from the Ministry of Health near the Eiffel Tower to the Senate at Luxembourg Gardens. Their objective: to "save medicine" by doubling the price of medical consultations from €25 to €50, extending their work week past 35 hours, and reducing the “pointless” paperwork they have to file on each patient.

On Wednesday, beet and cereal farmers, flanked by 500 tractors, marched from the Porte de Versailles, where the International Agricultural Show is scheduled for the end of February, to the Ministry of Agriculture at Invalides. They were protesting the decision of the Court of Justice of the European Union to ban the use of bee-killing neonicotinoid insecticides.

Thursday was the fifth protest march in less than a month against pension reform. In Paris the march went from the Place de la Bastille to the Place d'Italie. More than 300,000 people attended. Some carried placards and bullhorns, others hammers, crowbars and wooden sticks. Principally, however, it was a peaceful demonstration, one of 230 across France, backed by transport shutdowns and full sector strikes in energy, refineries, education, public service and health.

Similar numbers attended Saturday’s pension reform protests. These were twinned with the gilets jaunes weekly protests, held every Saturday around the country since November 2018.

There were others. At Place République, groups assemble most days, protesting everything from the actions of foreign governments to vaccination mandates, sexist violence, same-sex marriages, anti-LGBTQIA+, police brutality and « les agresseurs de forces de l’ordre » – aggression against the police.

The Women’s March on Versailles in 1789. The street risings during and after Napoleon. The massive support shown the provisional government during the 1848 revolution. The demonstrations for and against Algerian Independence in 1961 and 1962. Mai 1968. The manifs against the death of Malik Oussekine in 1986, and for the sans-papiers in the early 1990s. Against Juppé and Chirac’s proposed retirement reforms in 1995 and Sarkozy’s in 2010. In support of Charlie Hebdo and freedom of expression in January 2015, and against the jihadist attacks in November 2015.

The list is as long as the longest marches in the city’s history: the liberation of Paris in 1944; the World Cup victory in 1998; and the cortege to the Pantheon for Victor Hugo’s enterrement in 1885.

These collective actions are as much a part of French identity as baguettes, blocus and haute couture. And they are healthy. Just as not participating, choosing instead to go for a stroll on the Seine, or a run in the Buttes-Chaumont, or to sit at a café, drink a beer and write a Substack post, is healthy.

Except last week.

Because last week, Paris and 24 other French cities, from Calais in the north to Marseille in the south and Ajaccio on the island of Corsica, were placed on fine particle pollution alert.

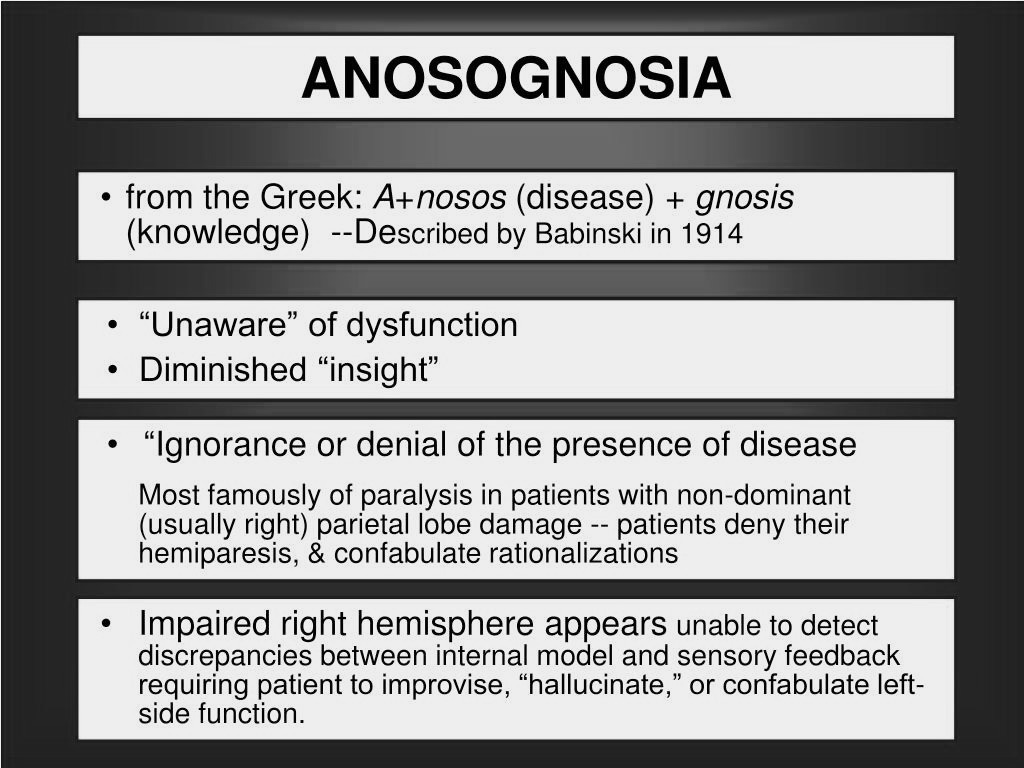

And this is where my Covid symptoms came from. And where my appropriation of the condition of anosognosia now comes into play.

There’s a fun piece in yesterday’s New Yorker by Marco Roth, a review of “The Great Easter: Ambulation,” a new English translation of La Grande Pâque (1969) by the French artist, poet, composer and Marxist activist Jacques Besse. Born in Paris in 1921, Besse was Jean-Paul Sartre’s star student until the war interrupted his studies and he turned to music, first as musical director of the Charles Dullin company (we discussed Dullin in our first Robert Cordier post in June). In 1943, Dullin reintroduced him to Sartre, who asked Bresse to compose the music for his play Les Mouches (The Flies). In 1944, his Concerto for Piano and Orchestra was performed at the Salle Gaveau. In 1947 he wrote the soundtrack for Alain Resnais’ film Van Gogh and befriended the otherwise friendless Pierre Boulez, who pushed his career forward.

In 1950, Besse went to Algeria to support the National Liberation Front. Something happened. A street brawl some say, and a consequent head injury; and then, according to legend, he walked all the way back to Paris, where alcohol and depression, already very much part of his world1, pulled that world fully apart.

The next five years were spent in “curious psychiatric internments" until Besse had himself admitted to the La Borde “anti-psychiatric” clinic in an old, ruined chateau in Cour-Cheverny, near Blois. There he lived, on and off, from 1955 till his death in 1999.

Besse was Félix Guattari’s patient at the clinic. Besse’s notebooks, according to his eventual publisher, Pierre Belfond - “covered with erasures and mistakes, torn, pasted back together, smudged, containing a mythical account of his nocturnal wanderings and those of his companions in misfortune: Villon, Sachs, Chabrier and Poe” – became a key source of Guattari’s explorations into the theory and praxis of schizoanalysis, best known in the anglophone world through Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Guattari’s 1972 book collaboration with the philosopher Gilles Deleuze.

La Grande Pâque is drawn from those notebooks. It is set in 1960, during an Easter week-long release from the clinic, when Besse, homeless and hungry, wandered through Paris “from Montparnasse to the Buttes-Chaumont, from Austerlitz to Sebastopol, passing through Singe-des-Prés [his hallucinatory “monkey” version of Boulevard Saint-Germain], the heart of the city.”

Here’s a taste of Besse’s dishevelled, feverish, jump-cut prose:

“I enter Singe-des-Prés like a herring flops. There is sin in the eggs if this warmth that grips my heart is contradicted. I bury myself in the streets south of the Seine. The Beaux-Arts district. Not a franc. I am terribly thirsty and don’t give a fluck2. I run into an old friend, he is a bourgeois but a good artist. “Do you have a hundred francs?” He's scared, the prick, but he lets me have it. I have a hundred francs and with exquisite pleasure set out in search of a bar.”

Besse pulls the reader along by the sleeve for 200 pages. He hallucinates encounters with various ex-lovers, drinks himself silly, steps into the path of cars and makes music out of their squealing brakes and shifting gears. And nowhere, at no point, does he think there’s anything wrong with him. And who’s to say there is? He’s just yet another self-absorbed flaneur in the streets of Paris, jotting down the minutiae of his semi-sleepwalking perambulations, unconcerned by the bigger picture, or any picture, other than those forming in the damaged quadrants of his frontal lobe.

All this to say… what? That a deficit of self-awareness is a bad thing? No more than a surfeit is. Except when it comes to a new form of pathology that I would like to draw your attention to.

Folie et déraison

When the “authorities” say “fine particles” they usually mean PM10 particles. The kind of particles that are obscuring our view of the Eiffel Tower in the photo above.

These, however, are not "fine particles". Fine particles are PM 2.5, and peaks of these are not as closely observed when air quality is measured. Because they’re too small. According to the French association Respire, “PM 2.5 fine particles are the most dangerous for health, but they are completely off the radar. There was a major pollution peak of PM 2.5 particles at the end of November, beginning of December. We saw nothing. Nothing was said. No measures were taken. We had big peaks of flu, bronchiolitis, Covid. We know that this is directly linked.”

Flu, bronchiolitis, Covid, these are short-term distractions. We now know what exposure to tiny, microscopic particulates does over the long-term. To every system in the human body across its lifespan. It damages prenatal and young brains. It damages everyone’s lungs, spleens, kidneys, hearts, brains and skin and other organs. It lessens academic performance and degrades impulse control. It causes cancer, asthma attacks and respiratory failure. It increases the risk of disease and disability across the board.

In short, it fucks us up. More than anything. In the States, annually, three times as many people die of it as die in car accidents. Twice as many as those that overdose on opioids. Many more than those that die of diabetes.

Worldwide, it kills seven million people annually. That’s more than the COVID-19 total to date.

It’s the biggest killer there is.

And what’s maddening is that we know how to make it go away. How to reduce millions of premature deaths, hospitalisations, emergency room visits and lost workdays, and save trillions. Relatively quickly. Pretty much effortlessly. All we have to do is demand that this be done.

But we don’t. Not because we’re in denial. Our lobes are probably too messed up to consciously choose denial. We don’t do anything because we don’t see the problem. Because we lack insight and awareness of our diagnosis.

Or maybe we see the problem but choose not to address it directly, which is worse, as it makes us no longer victims but perpetrators, complicit in wholesale death and massive suffering.

Or maybe it’s because we’re too focussed elsewhere: on our livelihoods, our retirement packages, our salaries. The size of our kids’ classrooms. All of which are undeniably important, but sort of at the level of Besse’s ex-lovers, really, in the grander scheme of things. They’re not quite matters of life and death. Or if they are, they need to first take a second seat to the more pressing life-and-death matter at hand. Which is the quality of the air we breathe.

We can do this. COVID-19 taught us, and is still teaching us, that we can do this.

What can I myself do on my own? I burst out laughing. – Jacques Besse

Professor Avenarius was lecturing me on the importance of slashing tires following a strict sequence: first car, right front; second car, left front; third, right rear; fourth, all four wheels. But that was only a theory with which he hoped to impress the audience of ecologists or his too trusting friend. In reality, he proceeded without any system whatsoever. He ran down the street, and whenever he felt like it he pulled out his knife and stuck it in the nearest tire. – Milan Kundera, Immortality, 1991.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not suggesting we follow the lead of Professor Avenarius and jog down Paris streets at night stabbing tires. Though there are more and more people around the world suggesting we do precisely this.

Have a look at the Tyre Extinguishers in the UK and the US, or Les Dégonfleurs in France.

Last week, two environmental activists were arrested in Sèvres in the Hauts-de-Seine. They allegedly deflated the tires of 200 SUVs and stuck flyers on their windscreens saying, “Your SUV is killing you”.

The couple face two years imprisonment and a 30,000 euro fine.

I’m not suggesting we follow their lead, either. Nor am I suggesting we join Extinction Rebellion or throw cans of soup at paintings.

I’m suggesting that the next time you see someone idling in the car because they are cold, listening to a podcast, or charging their smartphone, you tap politely on their windshield and tell them that they are breaking the law by unnecessarily defiling the air.

I’m suggesting that the next time you see an SUV or a 4x4 – by far the biggest CO2 emitters – point your finger and laugh at it, with as much scorn as you can muster, as if it is the puniest, most shrivelled up and ridiculous thing you’ve seen all day.

I’m suggesting that on the next day of moderate particulate pollution, we peacefully assemble, in numbers that dwarf World Cup celebrations and the funerals of literary lions, and demand that people and governments become aware that air pollution is a human rights violation, as unconscionable an atrocity as any perpetrated on this planet.

We need to find the wherewithal to throw wartime energies into the pursuit of decarbonisation. To insist that our representatives don’t just make recommendations but stick to our worldwide pledge to keep greenhouse gas emissions below 2°C.

We need to restrict fossil-fuel automobile use, heating and cooling for pleasure, supplementary heating, and wood heating in general – but especially, for starters, during peak periods of air pollution.

We need to incentivise clean energy technologies, walking, cycling, public transport, low-emission vehicles, electric vehicles.

We need to give medals to people who PASO (Put a Sweater On) and snuggle under blankets.

Whatever it takes.

We know all this. But we’re too busy flucking about to do fuck all about it. World Health Organization data shows that nine out of ten people breathe high levels of air pollution every day. Aggressive decarbonisation could cut the premature death toll that this causes almost in half within a decade.

Some effects of climate change look to be here to stay. But not air pollution. That we can wipe out. Country by country, reaping the social benefits locally each time.

Rien à foutre? Rien à floutre!

I’ll leave you with Jacques Besse still flucking about in Paris, no longer anosognosiac but fully aware of his affliction, and in the last paragraph on the last page of Keith Harris’s translation, which despite the misgivings expressed in the footnote below, I heartily recommend:

What can I myself do on my own? I burst out laughing. I begin surreally, shall I say in a dream, to speak of Algeria’s independence, I’ll just repeat that I was mad, I’ll say that I went mad in 1954, I’ll just repeat what will end up being accepted as soon as enough terrible years have passed, paying a demon for each of our faults, faults perhaps analogous to what makes me, me, the Mars-Jacques Besse of today, come back down into politics, into prosaic politics, the same way that I want to throw myself into prosaic poetry the day after tomorrow. And walking back to Saint-Germain-des-Prés on autopilot, I wonder what burden of Love, what tax on love that isn’t the tax of blood, we will have to pay for the poverty of all our prosaic acts at the gates of the heaven that invites us, we, the most absurd of people, into the most poetic of Alliances!

Prosaic politics. As necessary as the air we breathe.

Thank you for reading. Please comment, share, like, subscribe – whatever prosaic act grabs you most.

According to Annie Cohen-Solal's biography, Sartre: A Life (1987), Sartre's daily intake during this period included "two packs of cigarettes and several pipes stuffed with black tobacco, more than a quart of alcohol – wine, beer, vodka, whisky, and so on – two hundred milligrams of amphetamines, fifteen grams of aspirin, several grams of barbiturates, plus coffee, tea, and rich meals."

The line in the original is rien à foultre. Bresse’s book was only published once, in 1969, and before that in the pages of Guattari’s journal Recherches in 1966. So foultre could be a typo for rien à foutre (“not to give a fuck”). Or it could be the Breton word foultre, which is an onomatopoeia expressing pleasant astonishment. I’ve decided to leave it somewhere in the middle. The translation, by Keith Harris, strays too far from the original for my taste. Besse’s writing is clipped and jolting fast, filled with weirdness, and best left that way.

I enjoy securing my five-point harness for Mr. Mooney's submissions, where we careen down disparate roads of histories and personalities that converge like stock cars in a plaza of reconciliation.

We here in Canada seem to be like the good Germans of a century ago, tucking our heads into our shoulders, putting in our earbuds and praying to hold on to our membership cards to the middling class.

I almost wish we had capacity to protest and resist anything on this side of the pond, with at least as much energy as the only ones collecting – the flag-wavers celebrating their ignorance like drunken frat boys, once again coming out of the beer halls.

We are so quick to convene the Coalitions of the Willing when it comes to war. How about a mass buying group, a Green Coalition, that is willing instead to forego just a little of its ultimate ability to consume in order to buy only from member countries who prove – not talk about and wring their hands over – a tangible program to improving the health of the planet. Start with the easiest to measure: fossil fuel consumption per capita, etc.

We don’t need to jump out of planes with daggers in our teeth as did our forbearers to meet the challenge of a global threat, just accept that through the embargo of non-compliant countries, our consumer goods might get just that little bit more expensive.

That is the big sacrifice asked of us today - in not a War on Pollution, just a Mild Inconvenience on Ecological Destruction.

Great writing and éducation. My mother began telling folk to stop idling 30 years ago. And Paso is the way to go. I do like to burn wood in my chimney, but do not do it often. Ambiant moments for spécial occasions.